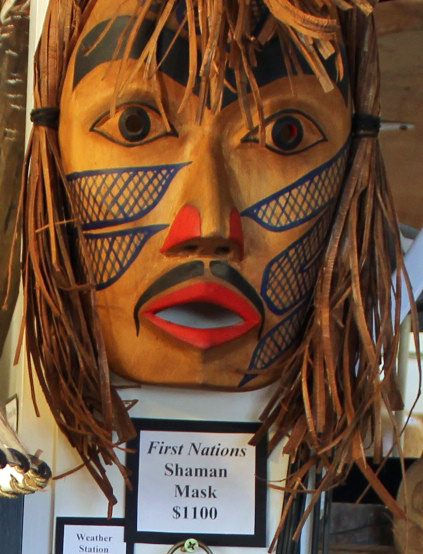

First Nations Shaman Mask

$1,000.00

First Nations Shaman Mask is carved of Red Cedar and decorated with fine blue and red paint touches and cedar raffia topknot. Now priced at $1000 (was $1100.)

10h x 8w, 12h includes the raffia.

The artist is a member of Chehalis First Nation and is a Master Carver, Master Seaman, and Hull Technician.

The Chehalis First Nation, or Sts’ailes Indian Band, is the band government of the Sts’Ailes people, whose territories lie between Deroche and Agassiz, British Columbia. There is evidence of this culture in the form of lithic (stone working) and mortuarial practices going back at least 1500 years.

In Sts’ailes tradition, Xals, the Transformer, defeated a powerful shaman known as “the Doctor”. Xals turned the shaman to stone, and broke the stone to pieces, spreading the fragments to prevent his return. The heart of the shaman fell on the shores of the home lake (Harrison Lake), and became the place where the Sts’ailes originated.

The name Sts’ailes means “beating heart”, which became the name of their village, located on the west side of the Harrison River. Their usual English name, Chehalis, is identical to that of the much more numerous Chehalis people of southern Puget Sound in Washington. By Sts’ailes tradition, the southern Chehalis were separated from their homeland as a consequence of the legendary Great Flood.

Among some First Nations, religion centered almost wholly in shamanism and there were no ceremonials unconnected with it. Shamans were the essential intermediaries between human and natural forces. Women could also become shamans among Northwest Coast tribes. Male or female, the shaman was the central religious figure, preeminently able to bridge the boundaries between mortals and spirits.

The shaman’s initial call was widely considered involuntary, even violent. The shaman may acquire powers by killing a supernatural being. But among some peoples the shaman-to-be is the spirits’ unwilling prey, vainly fleeing a summons he cannot refuse. One shaman told of how he strove to escape from a large owl that tried to carry him away, and tall trees that crawled after him like snakes, and how he resisted the visionary shamans who bade him join them, until finally “I began to sing. A chant was coming out of me without my being able to do anything to stop it.”

Despite some tradition of automatic inheritance of shamanic powers, for most Northwest Coast shamans neither inheritance nor involuntary seizure was sufficient preparation unless followed by a prolonged solitary quest culminating in personal encounter with the empowering spirits. Among many tribes from southern British Columbia to northern Oregon, notably the Coast Salish, the quest was the central spiritual experience of each individual shaman’s life.